This year’s largest stock sale didn’t happen on Wall Street. It was OpenAI’s $40 billion private share offering, open only to fewer than 50 elite investors, handpicked by Sam Altman and his executive team. While billionaires and hedge funds bought in, ordinary Americans were locked out.

The gap between public and private investing in the US is widening fast. The number of publicly listed companies has dropped by half since the late 1990s, while private deals are flourishing among the ultrawealthy. The result is a two-tier market: insiders gain early access to booming startups like SpaceX and Databricks, while the rest of the public gets slower-growing, already mature companies.

Even Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) Chairman Paul Atkins warns this is becoming a threat to economic fairness. He’s pushing reforms to open private markets to more investors, arguing that ordinary Americans deserve access to early-stage growth. “Why should ordinary investors be closed off in so many ways?” Atkins asked in an interview.

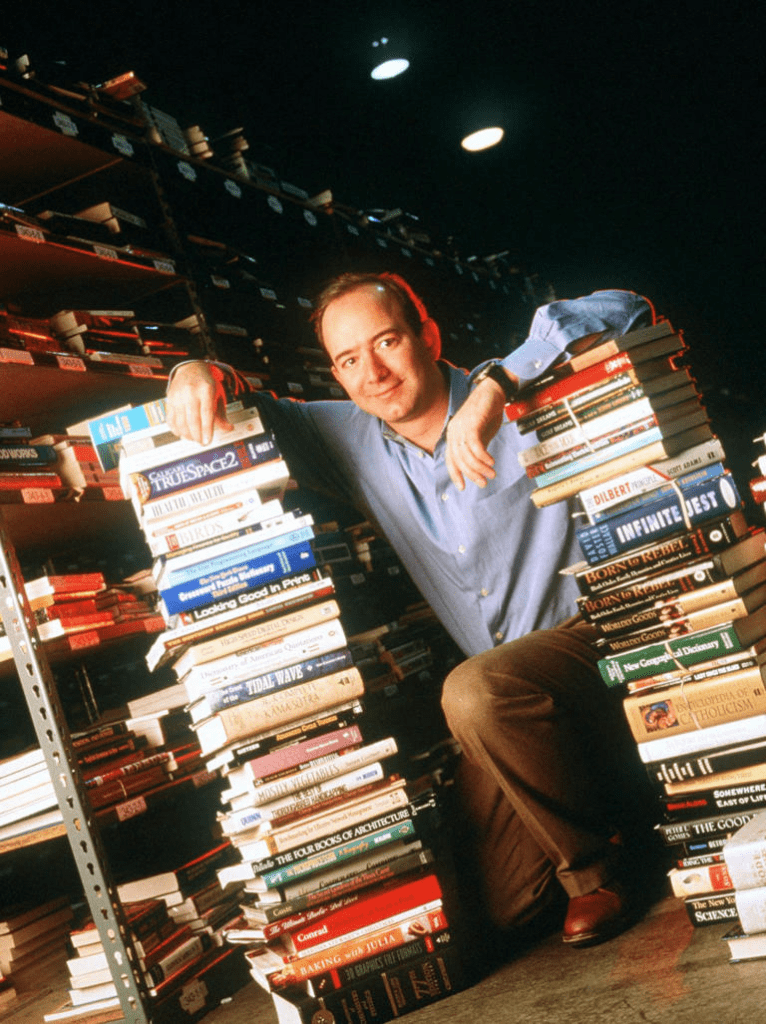

For decades, IPOs were a symbol of opportunity. When Amazon went public in 1997, everyday investors could buy shares at $18, long before it became a trillion-dollar giant. But today’s startups, like Figure AI, which jumped from a $2.6 billion to $39 billion valuation in under two years, raise billions privately, often from names like Jeff Bezos or SoftBank, before retail investors ever get a chance.

Meanwhile, SpaceX now tops $800 billion in private valuation, with early insiders earning massive returns. Musk’s firm may eventually go public, but ordinary investors have already missed the biggest gains.

To access these private shares, investors must be “accredited”, meaning a net worth above $1 million or income over $200,000, and even then, only a select few are invited into these exclusive rounds. Others rely on special-purpose vehicles (SPVs) managed by firms like Valor Equity Partners or brokers such as UBS, often with layered fees and little transparency.

Critics say this opaque system is rife with risks and fraud. The SEC is investigating platforms like Linqto, which allegedly misled small investors into thinking they owned shares of companies like Ripple and SpaceX, when they didn’t.

Still, Wall Street sees opportunity. Charles Schwab, Morgan Stanley, and Nasdaq Private Market are all moving to expand access to private-company shares, positioning themselves for what Schwab CEO Rick Wurster called “a huge market.”

If Atkins succeeds, it won’t mean a seat next to Sam Altman or Elon Musk, but it could mean a safer, regulated path for smaller investors to join the private-market boom.

Until then, the reality remains: the rich get richer, one private deal at a time.

Disclosure: This article does not represent investment advice. The content and materials featured on this page are for educational purposes only.